Katie King

Women's Studies, University of Maryland, College Park

Hello. My name is Katie King. Lots of people around here know that I do work on Science Fiction and on television, but few of them know many specifics about that work. Tonight I am going to give you an introduction to what I am calling "Star Trek Media Art" in honor of the exhibition that has just opened at the Art Gallery, here at the University of Maryland. The

exhibition is entitled possiblefutures: science fiction art from the Frank collection. I am indebted to the Art Gallery for inviting me to speak tonight, and to the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities for this semester's fellowship to explore these and other meanings of art and technology, and for various kinds of help with this presentation; my thanks to David Silver in particular. I am also indebted to my own Women's Studies Department, for releasing me this semester to take advantage of the fellowship and for valuing the work that I do, a sample of which you will hear tonight. My talking and showing you film clips should altogether take about an hour.

exhibition is entitled possiblefutures: science fiction art from the Frank collection. I am indebted to the Art Gallery for inviting me to speak tonight, and to the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities for this semester's fellowship to explore these and other meanings of art and technology, and for various kinds of help with this presentation; my thanks to David Silver in particular. I am also indebted to my own Women's Studies Department, for releasing me this semester to take advantage of the fellowship and for valuing the work that I do, a sample of which you will hear tonight. My talking and showing you film clips should altogether take about an hour.

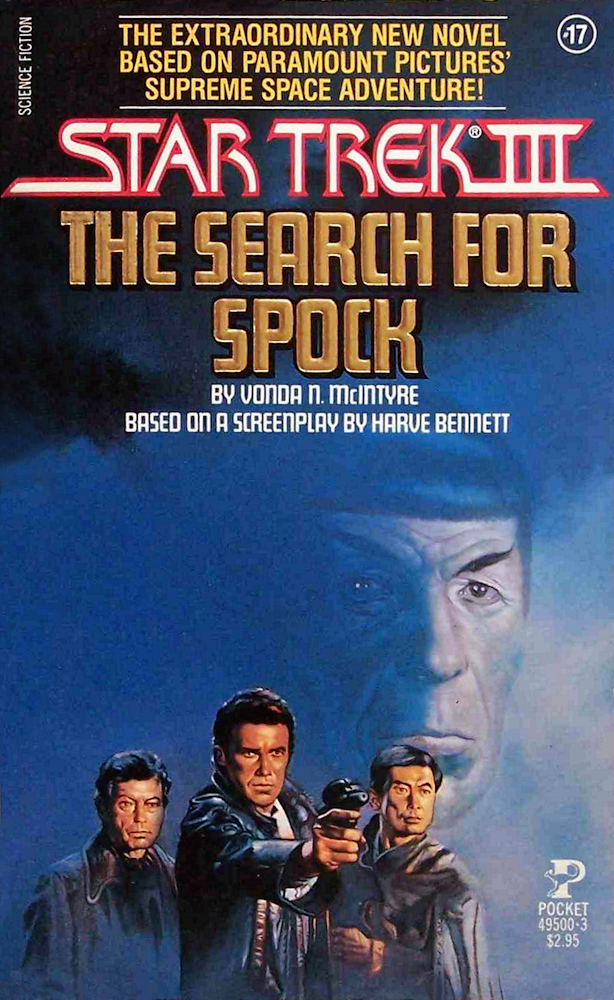

First, I am going to say something about Why Science Fiction Matters: what it is and a bit of its history in the U.S. Long-time fans refer to Science Fiction as SF, and I will also use this short hand tonight. Next, I will explain a bit about How Cultural Studies Helps Us Make SF Meaningful: how to put it in the context of literary pleasure, of commercial production, and also how to appreciate the interactive possibilities it offers. After that I will specifically discuss the various venues in which one culturally powerful version of SF, Star Trek, has taken form; in illustration I will focus on the film and the novelization both entitled The Search for Spock. My goal in contrasting the film and the book will be to give you a rich example of some of the interactive possibilities of media art, an example that highlights issues of gender and of intervention into mass culture. Finally, I will conclude by reflecting a bit on Media Art and Social Change.

Why Science Fiction Matters

For those of us who just like SF, answering the question Why SF Matters may seem superfluous. But for others, the very effect that makes SF particularly meaningful may be the very reason they avoid it. SF scholars call this effect defamiliarization, or estrangement. It is the discomfort my students often express when they say they don't like SF because "It's not real." Well, of course they love other "not real" things: melodramatic fiction for example, which suggests that they are groping after good words to express their distaste. When they've had an opportunity to desensitize themselves to this estrangement effect, they often discover that SF is not at all what they thought it was. At first when they find themselves liking something SF they have a tendency to say, "Well, that's not really Science Fiction!" But, of course, it is, it's just that the range of examples they've encountered has been rather narrow. However, tonight we will be exploring Star Trek SF particularly, and some here might feel that rather than being unfamiliar, Star Trek is OVER familiar! Having encountered it on the run as it were, they may think they know it and find it boringly familiar indeed. Additionally, some fans of literary SF sometimes feel that media SF and its fans are disrupting the pleasures they consider central to Science Fiction. You will see in this talk that I analyze literary SF and media SF together, and you can judge for yourself how well doing that works.

But really how different are the worlds of SF? What are the limits of our imaginations of difference itself? This is the kind of question that those of us interested in cultural change ponder examining SF, for in fact much of it does replicate the very aspects of culture and society we find at the root of injustices of various kinds. Utopian visions are only one aspect of one kind of Science Fiction, although they are often pointed to in discussions explaining it. But other elements of SF are at least as interesting, and much more contradictory and ambiguous.

But really how different are the worlds of SF? What are the limits of our imaginations of difference itself? This is the kind of question that those of us interested in cultural change ponder examining SF, for in fact much of it does replicate the very aspects of culture and society we find at the root of injustices of various kinds. Utopian visions are only one aspect of one kind of Science Fiction, although they are often pointed to in discussions explaining it. But other elements of SF are at least as interesting, and much more contradictory and ambiguous.

Let's start off from another angle then, from a distinction that SF scholar, Samuel R. Delany, makes in his 1984 collection of analytic essays Starboard Wine. Also known as "Chip," Delany is one of the relatively few African American writers of SF, known as part of the 60s literary revolution in SF called "The New Wave." Delany has always explored issues of sexuality, racism and sexism in his work, literary, critical and theoretical. Like another African American SF writer, Octavia Butler, Delany started writing SF as a teenager and as a fan. SF fans divide fiction into two forms: so-called "mundane fiction" and "science fiction." Delany describes a critical difference between them by using the sentence "Then her world exploded." Notice that in mundane fiction "Then her world exploded" is a powerful metaphor. It describes a psychological state of disruption, and/or a material state of utter chaos. But in Science Fiction, the sentence is not only metaphoric but literalized. Think of Princess Leia in the movie Star Wars, standing on the deck of the Death Star, taunted by Grand Moff Tarkin, watching helplessly as her home world, the planet Aldaraan, explodes before her eyes. [show #1 Star Wars clip] But of course, Star Wars is "not real." We are not standing on the deck of the Death Star, however much the movie-viewing experience, or the SF reading experience, puts us there in imagination. This literalization doesn't take place in our world. For a moment we live simultaneously in two worlds through this literalization process.

This flickering simultaneously in fantasy and reality is a subject for much joking among SF fans and in SF itself. It ranges from the simple but satisfying ironies expressed in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, in the sequence some call "Mr. Adventure," to the complex difficulties of one of my favorite episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, entitled "Far Beyond the Stars."

===

===

Indeed, the whole of the recent movie Galaxy Quest is an elaborate joke about this literalization process and about Star Trek fandom.

===

===

Indeed, the whole of the recent movie Galaxy Quest is an elaborate joke about this literalization process and about Star Trek fandom.

I wanted to show you the trailer for the "Far Beyond the Stars" episode of Deep Space Nine that I got off the web, but snow days cut into our tech time, so instead on the handout I gave you the web address so you can go look at it yourselves, and see this image from the episode. The real reason I love this episode is that it folds into itself the conditions of production of US science fiction that created some of its literary, commercial and interactive effects, and dramatizes them as raced.

===

===

Doing so then allows us to imagine how such processes are also gendered. With this in mind, let me give you a snippet of history of one important strand of literary SF as a history of commercial production. To do so, we will start with the issue of naming, of pseudonyms and of the use of the Generic "Man." Writing SF for the pulp magazines of the 30s, 40s and 50s meant writing short stories that were paid for by the word. Years ago I was examining the

papers of SF writer Robert Heinlein at the special collections of the University of California, Santa Cruz. At that time none of this material was cataloged or much examined; I was myself a student really just wanting to actually handle the manuscripts of my once favorite SF author. Looking at them I saw there were little numbers in pencil at the top of each page, but they weren't page numbers. I asked the librarian what they were, but frankly the librarians were uninterested in what was then a newly acquired collection. After looking at many manuscripts of various short stories it finally dawned on me: these were word counts for each page, because each story was paid for by the number of words. It vividly brought home to me how little money one made per story. As an SF writer, even though you were paid so little money that you couldn't live on your writing if you weren't publishing many stories each month, they didn't want one author publishing many stories in each issue of a particular magazine. So the same author might write under several names in order to do just that, perhaps each name specializing in a particular kind of story or a particular series of characters.

===

===

Doing so then allows us to imagine how such processes are also gendered. With this in mind, let me give you a snippet of history of one important strand of literary SF as a history of commercial production. To do so, we will start with the issue of naming, of pseudonyms and of the use of the Generic "Man." Writing SF for the pulp magazines of the 30s, 40s and 50s meant writing short stories that were paid for by the word. Years ago I was examining the

papers of SF writer Robert Heinlein at the special collections of the University of California, Santa Cruz. At that time none of this material was cataloged or much examined; I was myself a student really just wanting to actually handle the manuscripts of my once favorite SF author. Looking at them I saw there were little numbers in pencil at the top of each page, but they weren't page numbers. I asked the librarian what they were, but frankly the librarians were uninterested in what was then a newly acquired collection. After looking at many manuscripts of various short stories it finally dawned on me: these were word counts for each page, because each story was paid for by the number of words. It vividly brought home to me how little money one made per story. As an SF writer, even though you were paid so little money that you couldn't live on your writing if you weren't publishing many stories each month, they didn't want one author publishing many stories in each issue of a particular magazine. So the same author might write under several names in order to do just that, perhaps each name specializing in a particular kind of story or a particular series of characters.

In the "Far Beyond the Stars" episode of DS9, space station Captain Sisko finds

himself unaccountably in another time and place, living the life of a man, Benny Russell, who writes for a 50s pulp SF magazine similar to several you can see in the exhibition. Go

look at Allen Anderson's War Maid of Mars, for example; it was an illustration for a 1952 issue of Planet Stories. Russell discovers that his editor considers the hero of his stories -- black space station captain, Benjamin Sisko (who Russell knows is "real") -- too unbelievable to publish Russell's work. (When you look through the exhibition at the 50s pulp covers, you’ll notice immediately how "believable" all those characters are!) Women SF authors encountered similar problems with sexism and racism in the course of their careers. Their editors told them that no one would read SF written by women, so they strategically used male, ungendered or ambiguous pseudonyms to hide their sex. Some heterosexual couples wrote SF together and published under single male author names too. Thus, author names in SF may multiply individual writers, can transform or make deliberately ambiguous gender, and sometimes create collaborations in various social strategies of production.

look at Allen Anderson's War Maid of Mars, for example; it was an illustration for a 1952 issue of Planet Stories. Russell discovers that his editor considers the hero of his stories -- black space station captain, Benjamin Sisko (who Russell knows is "real") -- too unbelievable to publish Russell's work. (When you look through the exhibition at the 50s pulp covers, you’ll notice immediately how "believable" all those characters are!) Women SF authors encountered similar problems with sexism and racism in the course of their careers. Their editors told them that no one would read SF written by women, so they strategically used male, ungendered or ambiguous pseudonyms to hide their sex. Some heterosexual couples wrote SF together and published under single male author names too. Thus, author names in SF may multiply individual writers, can transform or make deliberately ambiguous gender, and sometimes create collaborations in various social strategies of production.

Another SF writer of the 60s New Wave, Joanna Russ, plays with these naming stratagems in her pivotal 1975 SF novel, The Female Man. The four heroines of the novel are genetically the same, but living in different kinds of societies at different historic moments, and are thus dramatically different people. Each has a different name starting with the letter J. "Janet" is from a lesbian utopian future, made possible by, in its distant past, the death by disease of all the men of her planet, Whileaway. "Jeannine," is from an alternative present, created when in her reality the US never entered WWII and the Great Depression never ended. "Jael" is from a far alternative future in which the so-called "War Between the Sexes" has become deadly literal, and women and men are engaged in catastrophic battle. The fourth J is "Joanna," who is from our own time, and who is the author of the book, Joanna Russ. She is the one who in a shimmering joking literalization has enfolded into her own story.

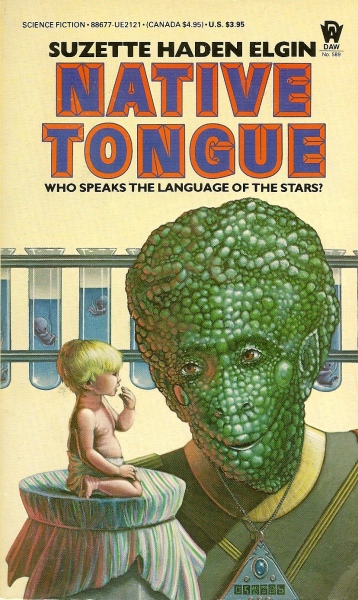

The title of the novel is another joke, this one about what linguists call "the Generic Man," that is, the word "Man" when it actually means "all human beings," and the absurdities produced when women ask whether they are included in terms that are supposed to be generic but really aren't: (I quote from Russ' novel): "...whoever heard of Java Woman and existential Woman and the values of Western Woman...? ... I think you will write about me as a Man from now on and speak of me as a Man and employ me as a Man and recognize child-rearing as a Man's business.... Listen to the female man." (p. 140) Similar feminist jokes are found in SF of the mid-80s. For example, Suzette Haden Elgin takes up Russ' sarcastic

comment about recognizing child-rearing as a Man's business, and shows us what the world might look like when child-rearing is the most important economic activity in interplanetary trade, and under the control of men, in her book Native Tongue. (I just had to get that in somehow because a cover for Native Tongue is one of the few works of SF art in the exhibition by a woman. Go look for it. The artist is Jill Bauman.) In this world children are reared to have multiple native languages, which they learn as babies in an interface with an alien native speaker, as depicted in Bauman's illustration.

The title of the novel is another joke, this one about what linguists call "the Generic Man," that is, the word "Man" when it actually means "all human beings," and the absurdities produced when women ask whether they are included in terms that are supposed to be generic but really aren't: (I quote from Russ' novel): "...whoever heard of Java Woman and existential Woman and the values of Western Woman...? ... I think you will write about me as a Man from now on and speak of me as a Man and employ me as a Man and recognize child-rearing as a Man's business.... Listen to the female man." (p. 140) Similar feminist jokes are found in SF of the mid-80s. For example, Suzette Haden Elgin takes up Russ' sarcastic

comment about recognizing child-rearing as a Man's business, and shows us what the world might look like when child-rearing is the most important economic activity in interplanetary trade, and under the control of men, in her book Native Tongue. (I just had to get that in somehow because a cover for Native Tongue is one of the few works of SF art in the exhibition by a woman. Go look for it. The artist is Jill Bauman.) In this world children are reared to have multiple native languages, which they learn as babies in an interface with an alien native speaker, as depicted in Bauman's illustration.

As a final point concerning SF histories, I want to mention that within this US history of pulp magazines, short stories written by the word, and collaborative productions, one form of SF novel came into being with the 1952 publication of

Clifford Simak's City. This form, the compilation novel, was created by a fan press, Gnome, which gathered all the short stories Simak had written around a particular theme and setting, and published that compilation as a novel. Take a look at Paul Lehr's 1991 cover illustration of a recent reprint of City when you tour the exhibition. Joanna Russ' 1983 The Adventures of Alyx is a similar compilation novel. This fascinating collaboration with oneself also has strange literary effects. The continuity of characterization especially is missing, and Russ' Alyx is oddly different from story to story, eerily capturing a feminist postmodern sensation of fragmented subjectivity.

Clifford Simak's City. This form, the compilation novel, was created by a fan press, Gnome, which gathered all the short stories Simak had written around a particular theme and setting, and published that compilation as a novel. Take a look at Paul Lehr's 1991 cover illustration of a recent reprint of City when you tour the exhibition. Joanna Russ' 1983 The Adventures of Alyx is a similar compilation novel. This fascinating collaboration with oneself also has strange literary effects. The continuity of characterization especially is missing, and Russ' Alyx is oddly different from story to story, eerily capturing a feminist postmodern sensation of fragmented subjectivity.

How Cultural Studies Makes SF Meaningful

One set of methods I use to think about SF comes from the field of cultural studies, which is less interested in what makes an art work "good," and more interested in how cultural products are part of cultural processes (getting around that value-laden term" art"). Science fiction, mysteries, romance novels, movies and TV are some of the cultural products studied, all of them deeply commercial forms of entertainment and often produced in complicated technical collaborations rather than seemingly simple single authorships. Genre and formula are intrinsic to the ways these products are produced and the ways they are enjoyed. In this context the term "genre" refers to a particular kind of writing, like SF or mystery or romance, say, and the conventions or formulas that create it. What is particularly pleasurable about such genre writing is not something that makes it unique, but rather the formulas that make it part of a series of various kinds; not something that happens only one time, but rather the very subtle shifts possible across many repetitions. Interestingly enough, such structural variations and their pleasurable effects are similar to those found in myths, in folk tales, in ancient epics, and in other pre-modern literary forms. I started off studying epic poetry myself, while Joanna Russ is a scholar of medieval literature in her academic incarnations, and Chip Delany is a Lacanian psychoanalytic theorist in his.

Authors and audiences are not easily separated when we focus on genre and formula and their complex collaborative repetitions. Thus, it is not surprising that complicated interactions are possible in the making of these kinds of cultural products. Elaborate fandoms, socially organized groups of fans, proliferate around genre products. Star Trek's fandom is culturally legendary, sometimes called Trekkies or Trekkers. During Star Trek's first 1966 season I became an ardent 14 year old fan myself. I used to audio tape each episode and listen to the voices over and over in my bed at night, until I had the dialog memorized. My cousin Amy was my fellow fan, and we wrote long letters about each episode several times a week, coast to coast, analyzing each in great detail, and writing out particularly memorable bits of repartee. For myself I wrote out fantasy stories in which I appeared in the Star Trek world and interacted with its inhabitants. These are all activities characteristic of fans, and in collectivities of fans--the "fandoms"-- to which I had no access in 1966, these activities are social and collaborative. Today many of these activities occur on the internet and the world wide web, and the technologies fans use in their informal publication and production efforts range from xerox and art work, to computer and digitized video. Fan writing may be circulated in informal friendship groups, in xeroxes sold at fan conventions--called "cons," in web sites and list serves, and in homemade videos reengineered with various apparatus.

And gender plays some roles in these fan forms as well. SF literary fandoms, around since the 30s and all along international, have tended to be dominated by male fans. SF media fandoms, first really organized around Star Trek in the late 60s, early 70s and increasingly international, have tended to be dominated by female fans. "Poaching" is the term some cultural critics use to describe how fans and fandoms appropriate commercial products for their own informal uses, altering their meanings, including themselves, and shifting the frames of representation. When we look at The Search for Spock we'll see an example of how such poaching operates.

And gender plays some roles in these fan forms as well. SF literary fandoms, around since the 30s and all along international, have tended to be dominated by male fans. SF media fandoms, first really organized around Star Trek in the late 60s, early 70s and increasingly international, have tended to be dominated by female fans. "Poaching" is the term some cultural critics use to describe how fans and fandoms appropriate commercial products for their own informal uses, altering their meanings, including themselves, and shifting the frames of representation. When we look at The Search for Spock we'll see an example of how such poaching operates.

The Worlds of Star Trek

In my own research I've spent lots of time looking at what I call "commercial exuberance." Commercial exuberance has a variety of forms. One way you can see it is in the myriad products now produced by what are called "media franchises." Star Trek is one such franchise. These franchises take advantage of the structure of multinational corporations. One such corporation may include as products and services: film and tv production, book, music and video publishing and distribution, theme parks, theaters, book stores, and so on.

So, Paramount's franchise versions of Star Trek include not only the four tv series (five if you count the animated series) and the nine films, but also tie-in novels and coffee table books (such as these I have up here), graphic novels, toys and games, other paraphernalia such as telephones, t-shirts and porcelain plates, music, commercial internet sites and catalog buying, and even scholarly works (such as these I brought along too!) But if you go to a Star Trek convention you will find not only all this commercially produced stuff, but also products fans have made themselves: xeroxed "fanfic," that is fiction written and self-published by fans, fan art work and various kinds of homemade stuff: buttons, clothing, jewelry, and so on.

So, Paramount's franchise versions of Star Trek include not only the four tv series (five if you count the animated series) and the nine films, but also tie-in novels and coffee table books (such as these I have up here), graphic novels, toys and games, other paraphernalia such as telephones, t-shirts and porcelain plates, music, commercial internet sites and catalog buying, and even scholarly works (such as these I brought along too!) But if you go to a Star Trek convention you will find not only all this commercially produced stuff, but also products fans have made themselves: xeroxed "fanfic," that is fiction written and self-published by fans, fan art work and various kinds of homemade stuff: buttons, clothing, jewelry, and so on.

The kind of commercial media art that Star Trek exemplifies is not understood as valuable and pleasurable because there is only one unique version of it, it is not an object that is autonomous, as some folks say, "Art for Art's sake," but quite the opposite. Instead this media art is pleasurable precisely because one instance of it is always insufficient in a very palpable way. That it is "not enough" in itself is precisely what makes it interactive and makes its production something that is an on-going, multiply collaborative process. In fact you might think of media art not as objects exactly but instead as processes, in which people engage in varying degrees and forms of intensity and with varying collaborative possibilities. Fandoms are the

venues in which high intensities of engagement and collaboration occur, they are communities that enlarge the processes that such media art sets into motion. Such media art is valuable precisely because it is not sufficient in itself, but is inspirational exactly because so much is left out, so much needs to be changed, so much invites elaboration. The term "poaching" recognizes that this interactive engagement is culturally ambiguous in a society that values property and that values works of art as unique creations by single artists who own their product. For example, Paramount is always trying to maintain its copyright in Star Trek, and although most fan productions are not illegal infringements of such copyright, some are ambiguous in this regard, always pushing the envelope on what elements of Star Trek belong to whom.

The Search for Spock: film and novelization

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock was released by Paramount on June 1, 1984. It was written and produced by Harve Bennet, directed by Leonard Nimoy, and its special effects were created by George Lucas' company Industrial Light and Magic. It starred the principle actors of the original series; Gene Roddenberry, who had originated the idea and original series, was its executive consultant. All of these people and many many more were extremely important but in dramatically different ways in the production of this very complicated object. The term "author" or "artist" cannot capture the varieties of production and complex collaborations that such an object requires. A book version of the movie was also published in 1984 in conjunction with the film's release. We call such a book version a "novelization" rather than simply a "novel" because it did not precede the making the movie, but rather comes with it or after it, and because the movie is not based on it, but rather it is based on the movie. I chose this movie in order to discuss this specific novelization by feminist Science Fiction author Vonda McIntyre.

Pamela Sargent (who, by the way, will be a featured speaker in the roundtable on March 3 that is happening as part of other events in conjunction with the possible futures exhibition. Jane Donawerth, a feminist SF scholar here at College Park and one of the affiliate faculty of women’s studies will also be a speaker in that roundtable discussion)--Pamela Sargent wrote a description of Vonda McIntyre, whose work she included in her Women of Wonder anthology of SF by women. Sargent says she has "a B.S in biology and did graduate work in genetics, won a Nebula Award for [her short story] "Of Mist, and Grass, and Sand," and Nebula and Hugo awards for her second [1978] novel, Dreamsnake. [Nebulas and Hugos are the most prestigious literary prizes in Science Fiction]. Her short fiction has appeared in Orbit, Analog, the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction [these are the contemporary analogs to the pulp SF magazines of the past] and other magazines and anthologies. With Susan Janice Anderson, [in 1976] she edited an anthology of humanist science fiction by both men and women, [entitled] Aurora: Beyond Equality." Sargent then goes on to list eight more SF novels by McIntyre, written between 1975 and 1994. Conspicuously absent from this list are McIntyre's tie-in books, which include at least three movie novelizations and two original novels for Star Trek, and one for Star Wars.

If you read her other Star Trek movie novelizations, you’ll notice that the one she did for The Search for Spock is very different. The other two are fairly straightforward literary printings of the final screen version. But The Search for Spock is an interactive novelization, much more in the spirit of fan fiction and fan elaborations of media art. Why she wrote such a novelization only this one time, I don't know. But this novelization is especially interesting in what it demonstrates is left out of the movie, and in what creative choices it makes in putting new stuff in. By doing both these things, the novelization comments upon, criticizes and alters the movie. At the beginning of ST3 we have some re-viewed material from the preceding film, The Wrath of Khan, establishing the heroic death of Mr. Spock. The story then picks up its new threads with Admiral Kirk's voice over as he enters new material into his personal log and as the opening credits for the film finish. In contrast, in McIntyre's book, by the time we get to Kirk's log entry we have already read 82 pages, or almost a third of the book. McIntyre does a great deal more to create dense continuities, especially focusing on and detailing the psychological states of characters and the events that are the results of these states. For example, Scotty's nephew is killed at the end of ST2, another hero. He is never mentioned again in ST3, but Vonda McIntyre weaves the repercussions of his death and Scotty's sorrow and grief into her version of the story.

Similarly, Carol Marcus, one of the principle characters and scientists in ST2, who turns out to be the mother of Kirk's only son, who Kirk didn't even know existed until then, is not mentioned at all in ST3, but again McIntyre weaves her into the story. Indeed her explanations make clear why we don't see Marcus again in the film, while also making it clear that her actions have important effects on what we do see in the film, thus establishing what feminist theorists call her "agency" or effective action. Probably the reasons these characters were not included in ST3 has to do with budget constraints on actors' salaries, story decisions made for financial reasons. The resulting holes in the story are then the fertile sites for this interactive poaching.

Similarly, Carol Marcus, one of the principle characters and scientists in ST2, who turns out to be the mother of Kirk's only son, who Kirk didn't even know existed until then, is not mentioned at all in ST3, but again McIntyre weaves her into the story. Indeed her explanations make clear why we don't see Marcus again in the film, while also making it clear that her actions have important effects on what we do see in the film, thus establishing what feminist theorists call her "agency" or effective action. Probably the reasons these characters were not included in ST3 has to do with budget constraints on actors' salaries, story decisions made for financial reasons. The resulting holes in the story are then the fertile sites for this interactive poaching.

But McIntyre is even more sly and somewhat nastier than just that, including feminist jokes that ridicule Kirk's macho self-involvement and the militarism of all the Star Trek films. She does this by including story elements that were never part of either film, in this case that Carol Marcus had become lovers with one of the other scientists on Spacelab, where the Genesis device (the central concern of both films) was created. All the people on Spacelab had been tortured and killed by Khan in the earlier film, so McIntyre's novelizations' beginning deals not only with Scotty's grief, but also with Carol Marcus' grief for this terrible death of her lover. McIntyre shows several exchanges between Carol Marcus and Admiral Kirk in which Marcus tries to tell Kirk that her lover had died and in which his self-involvement is such that he thinks she is trying to suggest that they--Kirk and Marcus--become lovers. Both Kirk, and to some extent, William Shatner, are ridiculed in this rewritten version of events, and getting the joke concerning Shatner requires that one be in the loop about the gossip about Shatner's insensitive attempts to seduce leading ladies during the tv show's existence. So, not only does the McIntyre version create continuity, and criticize the gender politics of the plot, but it also points to extratextual information that add other gossip-y pleasures, and thus extend the range of possible interactions.

Similarly, SF generally speaking, and Star Trek specifically have been the subject of feminist and other SF criticism for their essential militarism. McIntyre has woven this also into the plot, making Kirk's son David the spokesperson for a critique of the Federation and its militarization of space and its appropriation of civilian projects. Later, though, in the film we find that David, as a scientist, has himself been unethical in his use of protomatter in the Genesis project, and he is taken to task by Spock's part Romulan-part Vulcan protégé, Saavik. This moment has additional layers of poignancy in McIntyre's version, where David and Saavik have become lovers, and Saavik's rebuke of David is filled with additional elements of longing, regret and betrayal. Indeed, it is through Saavik’s consciousness that we understand much of what happens in the novelization.

Let me show you then the final sequence from the film but tell you first about McIntyre's version of what you will see in the film, to give you some palpable sense of how this interactivity works. To fill in the film plot first, it turns out that Spock's katra or mind and soul have survived the death of his body and been entrusted to Dr. McCoy, without his knowledge. McCoy, not understanding what has happened, acts in ways he and others consider insane. David and Saavik have located Spock's body on the Genesis planet, where the Genesis device has reanimated it. David, Kirk's son, has been killed by the Klingons who desire to use Genesis as a weapon, which McIntyre reveals the Federation understands it to be also. The crew of the Enterprise has had to destroy their ship in order to prevent the Klingons from taking control of it, but have then themselves taken control of the Klingon vessel. In it they take McCoy, with Spock's katra, and the body of the animated but not fully conscious Spock, back to Vulcan, to have them fused together by T'Lar.

Let me show you then the final sequence from the film but tell you first about McIntyre's version of what you will see in the film, to give you some palpable sense of how this interactivity works. To fill in the film plot first, it turns out that Spock's katra or mind and soul have survived the death of his body and been entrusted to Dr. McCoy, without his knowledge. McCoy, not understanding what has happened, acts in ways he and others consider insane. David and Saavik have located Spock's body on the Genesis planet, where the Genesis device has reanimated it. David, Kirk's son, has been killed by the Klingons who desire to use Genesis as a weapon, which McIntyre reveals the Federation understands it to be also. The crew of the Enterprise has had to destroy their ship in order to prevent the Klingons from taking control of it, but have then themselves taken control of the Klingon vessel. In it they take McCoy, with Spock's katra, and the body of the animated but not fully conscious Spock, back to Vulcan, to have them fused together by T'Lar.

The first thing to notice in the film is the "look" of Vulcan, the staging of the set, the costumes and colors, and especially the appearance of the women taking part in the ceremony.

This look is based on early SF illustrations such as those done for Edgar Rice Burroughs' Maid and Princess of Mars books, books first published in the twenties. Notice particularly

the women wearing almost transparent gowns, virtually naked. The men and some of the other women are wearing clothes that cover them very completely, and in the film one has the impression these are the higher ranking folks. McIntyre ignores the men who we can clearly see in the film, and instead suggests that this Priesthood--never using the trivializing term "priestesses," which is more in keeping with the Burroughs’ associations--is entirely of women. This subtly alters the connotations of the scanty clothing on the women. Indeed the credits call T'Lar, the High Priestess, but McIntyre calls her the leader of the Vulcan Priesthood. McIntyre then accounts for an absence we may not have even noticed until she explains it: that of Spock's mother, Amanda. This is the second thing to notice. Spock's father, Sarek, has been a principle character in the film, but not his mother, and especially once here on Vulcan, at the resurrection of her son, her absence is amazing, even if we have not noticed it. Feminist critics of SF have long noted how invisible mothers are in science fiction, and how often men instead become quasi-mothers through technological means. McIntyre here is examining that thread in SF and altering it.

This look is based on early SF illustrations such as those done for Edgar Rice Burroughs' Maid and Princess of Mars books, books first published in the twenties. Notice particularly

the women wearing almost transparent gowns, virtually naked. The men and some of the other women are wearing clothes that cover them very completely, and in the film one has the impression these are the higher ranking folks. McIntyre ignores the men who we can clearly see in the film, and instead suggests that this Priesthood--never using the trivializing term "priestesses," which is more in keeping with the Burroughs’ associations--is entirely of women. This subtly alters the connotations of the scanty clothing on the women. Indeed the credits call T'Lar, the High Priestess, but McIntyre calls her the leader of the Vulcan Priesthood. McIntyre then accounts for an absence we may not have even noticed until she explains it: that of Spock's mother, Amanda. This is the second thing to notice. Spock's father, Sarek, has been a principle character in the film, but not his mother, and especially once here on Vulcan, at the resurrection of her son, her absence is amazing, even if we have not noticed it. Feminist critics of SF have long noted how invisible mothers are in science fiction, and how often men instead become quasi-mothers through technological means. McIntyre here is examining that thread in SF and altering it.

After reading McIntyre we know that Spock's mother Amanda is watching everything just as we see it, from a balcony overlooking the plain on which the refusion of Spock's katra and body will occur. She is an adept in the very discipline of which T'Lar is leader, but since she is mentally connected to Spock, as a relative, the very sensitivities that she has cultivated would now be a liability in the fusion process. Since Spock's father is at the ceremony, it follows from McIntyre's discussion that he is not an adept in this discipline. McIntyre writes: "She knew from the beginning that she could not be a member of the group that assisted her son. She understood the logic of avoiding such a completely unnecessary risk. But her intellectual acceptance of matters did absolutely nothing to diminish the emotional desire, her need, to be in the temple, to try to help....'If I weren't a student-adept, I wouldn't endanger Spock just by being near him! At least I could be down there! At least Sarek and I could be together tonight!'" (p292) Other rather subtle shifts in language take place in McIntyre's version of the events you will watch. They continually operate to include women as subjects and agents in a way that the film does not. So the third thing to notice is one very clear example of this, one of many, when McCoy speaks of himself as "son of David." In McIntyre he calls himself "son of David and Eleanora" and T'Lar repeats this.

Finally, let me elaborate something that not especially emphasized in McIntyre's book, but part of the world of some kinds of fanfic and of some kinds of Star Trek scholarship, that adds an interesting layer to the final reunion between Spock and Kirk in the film. At the beginning of the film, its middle, and at this end, Spock's final words to Kirk are emphasized, the theme of male friendship: "I am and always shall be your friend."

===

===

One segment of Star Trek fandom writes stories in which Kirk and Spock have been lovers as well as friends. In some ways this is a joke, especially at Shatner's expense, about Kirk's vigorous heterosexuality on the show. In other ways this is an elaboration of Spock's difference, and of the possibilities of alternate sexualities it opens up. According to the fan stories, Spock and Kirk became lovers first situationally, in order to save Spock's life, as he went through a Vulcan male estrus cycle calledpon farr, during which he must mate or die. In the fan stories Spock and Kirk are marooned together alone, and when Spock goes into pon farr there is only Kirk to mate with! Some stories emphasize this sacrificial dimensional of their sexual relationship, other stories emphasize its romantic elements. The original stories are often homophobic, if inadvertently so, but later stories of this type are closer to gay

sensibilities and reflect cultural changes over a couple of decades. Such stories are now so well known in Star Trek culture, not just fan culture, but by the producers, writers and actors as well, that they are now always an alternate story line whenever pon farr is mentioned, as it is in this film. For when Spock is recovered on the Genesis planet he does go through pon farr in the film, Saavik explains it to him and (presumably) mates with him off-camera and otherwise it is uncommented upon. However, just mentioning pon farr in the film, something the producers know is an audience pleaser because it is a many layered joke, raises alternate story possibilities along these lines which alters how some audiences hear the refrain of male friendship and celebrate it. Adding an even additional layer, literary SF people also enjoy the allusion, since the episode in which pon farr was first introduced in the original series was written by another very famous SF author, Theodore Sturgeon, known for his literary experiments in sexualities during The New Wave and the 60s. So remember the layers of pon farr when you hear "I am and always shall be your friend." So, these are things to watch out for in video clip: 1) notice how the meanings of "the look" are altered by McIntyre’s changes; 2) watch the events through Amanda’s consciousness as she witnesses them; 3) notice McCoy’s "son of David" and hear instead "son of David and Eleanora"; 4) appreciate the layers of meaning added to Spock and Kirk’s interaction by pon farr. [View Vulcan sequence near end of Search for Spock]

===

===

One segment of Star Trek fandom writes stories in which Kirk and Spock have been lovers as well as friends. In some ways this is a joke, especially at Shatner's expense, about Kirk's vigorous heterosexuality on the show. In other ways this is an elaboration of Spock's difference, and of the possibilities of alternate sexualities it opens up. According to the fan stories, Spock and Kirk became lovers first situationally, in order to save Spock's life, as he went through a Vulcan male estrus cycle calledpon farr, during which he must mate or die. In the fan stories Spock and Kirk are marooned together alone, and when Spock goes into pon farr there is only Kirk to mate with! Some stories emphasize this sacrificial dimensional of their sexual relationship, other stories emphasize its romantic elements. The original stories are often homophobic, if inadvertently so, but later stories of this type are closer to gay

sensibilities and reflect cultural changes over a couple of decades. Such stories are now so well known in Star Trek culture, not just fan culture, but by the producers, writers and actors as well, that they are now always an alternate story line whenever pon farr is mentioned, as it is in this film. For when Spock is recovered on the Genesis planet he does go through pon farr in the film, Saavik explains it to him and (presumably) mates with him off-camera and otherwise it is uncommented upon. However, just mentioning pon farr in the film, something the producers know is an audience pleaser because it is a many layered joke, raises alternate story possibilities along these lines which alters how some audiences hear the refrain of male friendship and celebrate it. Adding an even additional layer, literary SF people also enjoy the allusion, since the episode in which pon farr was first introduced in the original series was written by another very famous SF author, Theodore Sturgeon, known for his literary experiments in sexualities during The New Wave and the 60s. So remember the layers of pon farr when you hear "I am and always shall be your friend." So, these are things to watch out for in video clip: 1) notice how the meanings of "the look" are altered by McIntyre’s changes; 2) watch the events through Amanda’s consciousness as she witnesses them; 3) notice McCoy’s "son of David" and hear instead "son of David and Eleanora"; 4) appreciate the layers of meaning added to Spock and Kirk’s interaction by pon farr. [View Vulcan sequence near end of Search for Spock]

Media Art and Social Change: Conclusion

Let me conclude with some comments about Media Art and Social Change. You may have heard the widely known story that Nichelle Nichols, who plays Communications Officer Uhura (and who we saw in the Mr. Adventure sequence), tells about a conversation she had with Martin Luther King about Star Trek. She says that she had just decided to leave the show because she was tired of putting up with the sexism of the stories and with the trivialization of her character, when she was introduced to Martin Luther King at a social event. Thrilled to meet the great civil rights leader, she actually began to apologize to King for the use made of her character on the show when he stopped her and told her how gratified he and his family were whenever they watched it together, to see such a graceful and respected black character in this visualization of a possible future. When he heard she was thinking of leaving, he encouraged her to stay, to fight for the character and to appreciate how important this depiction was for the psyches of young black women and girls. You may even have heard that Whoopi Goldberg wanted to be on Star Trek: The Next Generation, where she played the alien Guinan, because as a young woman she had been so inspired by Uhura and wanted there to be a continuing black woman character of importance in this next series. Star Trek producers love to tell these stories too, and love to think of Star Trek as a beacon of antiracist thought and a 60s harbinger of multiculturalism. These stories do show that this is indeed one element of the complicated story lines and ambiance of Star Trek.

However anyone who has watched Star Trek for any length of time is also aware that racisms of all sorts are also elements of Star Trek stories, and clearly present in unreflected upon assumptions made by producers, actors, story writers, fans and so on. Like other kinds of SF Star Trek also often does replicate the very aspects of culture and society we find at the root of a range of social injustices, racism, sexism, homophobia, and others. Among fans and in the public at large you will hear people dispute these issues about Star Trek, some seeing it as antiracist and some seeing it as racist, each able to argue their points with both conviction and some powerful evidence, because in fact both of these political positions are always engaged in Star Trek.

From a Cultural Studies perspective Star Trek is hardly alone here, most cultural products are understood by cultural studies as complexly contradictory, full of progressive possibilities and also full of structures that shut down such possibility and reinforce inequalities. Scholarly books, such as (these I brought with me) Robin Roberts' 1999 Textual Generations: Star Trek: The Next Generation and Gender; Daniel Bernardi's 1998 Star Trek and History: Race-ing Toward a White Future; and the 1996 collection of essays Enterprise Zones: Critical Positions on Star Trek; these are all analyses of the cultural biases that, all too understandably, are at the very heart of the worlds created around Star Trek. But such biases are also subject to social change: creating it, reflecting it, and other more complex possibilities. Remember that the interactive possibilities of Media Art lie precisely in what it sets into motion: that it is inspirational precisely because so much is left out, so much needs to be changed, so much invites our remaking it.

At the beginning of ST3: The Search for Spock Kirk speaks Spock's funeral address and movingly says: [show clip: his soul was the most human].

===

===

Notice what the word "human" does here: it simultaneously creates unities across races and nationalities, just as it also valorizes and makes superior the species "human." In one sense it creates a new inequality: between humans and non-humans; in another it uses human as a universal term for courage and what we call "humanity" or compassion. And it is also an ironic appreciation of Spock's mixed cultural and species heritage. (Indeed, such references to Spock are a running joke throughout Star Trek.) This is an example of the kind of contradiction that cultural studies analyzes. These are cultural sites of struggles for power and for competing visions of justice. Understanding all the nuances of that matters to cultural studies scholars because such sites are understood to be places in which social change is possible, although never easy and never obvious how to be accomplished. Bernardi in Racing toward a White Future, examines the kinds of discussions fans have about social issues raised by Star Trek, and how some become activists in challenging the producers to change and shift Star Trek. The social changes possible within Media Art are both occasionally powerful and often very limited. But then again, social change on various fronts has some specific powers and many limitations. Assuming that we must only make big changes keeps us from valuing small ones and makes social change appear too difficult. On the other hand being too enthusiastic about changes that are very limited keeps us from being ambitious about what is politically possible. Media Art's interactive processes invite a kind of engagement and interaction that can be progressive and inspirational, but like all social change, although this is at times pleasurably so, it is always labor intensive. There are no short cuts to progressive change, but there are places that give us good reasons to hope and work at it. Sometimes, Star Trek is one of them. Thank you.

===

===

Notice what the word "human" does here: it simultaneously creates unities across races and nationalities, just as it also valorizes and makes superior the species "human." In one sense it creates a new inequality: between humans and non-humans; in another it uses human as a universal term for courage and what we call "humanity" or compassion. And it is also an ironic appreciation of Spock's mixed cultural and species heritage. (Indeed, such references to Spock are a running joke throughout Star Trek.) This is an example of the kind of contradiction that cultural studies analyzes. These are cultural sites of struggles for power and for competing visions of justice. Understanding all the nuances of that matters to cultural studies scholars because such sites are understood to be places in which social change is possible, although never easy and never obvious how to be accomplished. Bernardi in Racing toward a White Future, examines the kinds of discussions fans have about social issues raised by Star Trek, and how some become activists in challenging the producers to change and shift Star Trek. The social changes possible within Media Art are both occasionally powerful and often very limited. But then again, social change on various fronts has some specific powers and many limitations. Assuming that we must only make big changes keeps us from valuing small ones and makes social change appear too difficult. On the other hand being too enthusiastic about changes that are very limited keeps us from being ambitious about what is politically possible. Media Art's interactive processes invite a kind of engagement and interaction that can be progressive and inspirational, but like all social change, although this is at times pleasurably so, it is always labor intensive. There are no short cuts to progressive change, but there are places that give us good reasons to hope and work at it. Sometimes, Star Trek is one of them. Thank you.